- Home

- Violet Kupersmith

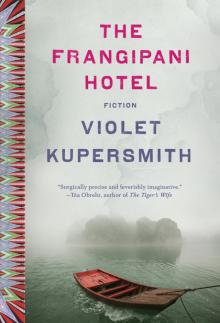

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction Read online

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2014 by Violet Kupersmith

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, New York.

SPIEGEL & GRAU and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Kupersmith, Violet.

[Short stories. Selections]

The Frangipani Hotel / Violet Kupersmith. —

First edition.

p. cm

ISBN 978-0-8129-9331-8

eBook ISBN 978-0-679-64514-6

I. Title. PS3611.U639F73

2013813’.6—dc23 2013013169

www.spiegelandgrau.com

Jacket design: Gabrielle Wilson and Greg Mollica

Jacket photograph: Thomas Backer/Aurora Photos

v3.1

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Boat Story

The Frangipani Hotel

Skin and Bones

Little Brother

The Red Veil

Guests

Turning Back

One-Finger

Descending Dragon

Dedication

Acknowledgments

About the Author

BOAT STORY

“HERE, CON, I CUT UP a đuđủ just for you.”

“Oh no, Grandma, I—”

“It’s very ripe!”

“Gra—”

“And very good for you too!”

“Grandma! You know I can’t eat papaya. It makes my stomach hurt.”

“Tck! It goes in the trash can then. Such a waste.”

“Wait! Why can’t you eat it? Or feed it to Grandpa?”

“Grandpa and I are sick of it—we’ve eaten nothing but đuđủ for two straight days because I bought six from that Chinese grocer out in Bellaire last week and now they’re starting to go bad.”

“Ha! Why did you buy so many?”

“I was hoping for visitors to share them with. But no one comes to see me. Everyone is too busy—so American! Always working, working, and no time for Grandma. Not even your mother stopped by this week. And the only reason you’re here is a silly high school project.”

“All right, all right. But I’m only gonna eat a bit, okay? Just this little piece right here. And then we’ll do the interview … Oh God, it’s so slimy …”

“Wonderful! Yes, chew, chew—”

“You don’t need to tell me to chew!”

“It’s disgusting to speak with your mouth full, con. Chew, chew. Swallow! See, that wasn’t so bad, was it? And it will make your hair shiny and give you good skin. Have another piece.”

“My stomach feels weird already, Grandma. But I’ll have one more piece while you talk, deal?”

“Oh, making deals now, hah? And I thought you weren’t sneaky like the other grandchildren. You’ll start gambling next. What kind of story did you want me to tell you, con?”

“I’m after the big one.”

“Oh dear.”

“Leaving Vietnam. The boat journey. That’s what I want to write about.”

“Ask your mother.”

“I did, but she was too young when it happened. She only remembers the refugee camp and arriving in Houston.”

“Ask your father then.”

“He came over on a plane in the eighties, and that’s not half as exciting. That’ll get me a B if I’m lucky. But your boat person story? Jackpot. Communists! Thai pirates! Starvation! That’s an A-plus story.”

“Oh, is that what it is?”

“Mom said you don’t like talking about the war, but I should know about my past, shouldn’t I? That’s what this school project is about—learning your history, exploring your culture, discovering where you came from, that kind of thing.”

“You really want to know the country you came from?”

“Yes.”

“And you want a story about me on a boat?”

“Yes!”

“Fine. I will tell you a boat story. It begins on a stormy day at sea.”

“Wait, wait! Let me get my pencil … Okay, go!”

“The waves were vicious, the wind was an animal, and the sky was dung-colored.”

“Hang on a second. Where were you?”

“On the boat, of course.”

“Well yeah, but is this 1975? We are talking about 1975, right?”

“Child, when you’re my age you don’t bother remembering years.”

“But this is at the very end of the war?”

“Did that war ever really end, con?”

“Look, Grandma, I just need to get the dates straight! How old were you then?”

“Around the same age as you; I married young. Perhaps a couple years older.”

“I think you’re getting confused. If Mom was seven when she left, you had to have been way older than sixteen.”

“Don’t be silly. I remember everything perfectly. This was the day after my wedding. My hair was long and shiny—it was all the đuđủ I ate growing up, I’m telling you, con—and my teeth weren’t bad; they said I could’ve made a better match than a fisherman. But I did not care about money. Even though we were poor, at the wedding I wore a silk dress embroidered with flowers, and gold earrings that my mother-in-law gave me. After the ceremony I gathered my belongings in a bag and moved onto Grandpa’s sampan.”

“Okay, we’re definitely not on the same page …”

“Quiet, con, you asked for my boat story, so now listen to me tell it.”

“YOUR GRANDPA SPENT OUR first night as husband and wife throwing up the two bottles of rice wine he drank at the wedding reception. In the morning his head was foggy, so he untied the boat and steered us out to sea without paying attention to the signs: the taste of the wind, the shape of the clouds, the strange way the birds were flying. He cast his nets but kept drawing them back empty, and so we drifted farther and farther from land. By the time he noticed how strong the waves were, we could no longer see the shore.

“The storm began, rain drilling down on us as we crouched together beneath a ratty tarp. Our poor sampan bounced on the water like a child’s toy. Waves sloshed over the sides, slapping me in the face, the salt burning my nostrils. When our tarp was torn away with a scream of wind, Grandpa and I dug our fingernails into the floorboards of the boat, even though we knew it would do no good in the end.

“ ‘When we are thrown into the water, cling to my back,’ Grandpa shouted, mostly to hide his fear. ‘I will swim us home.’ His breath was still stale with rice wine.

“But this boat is our home, I thought. I looked out over the waves that I knew would soon swallow us up. Then to my surprise, I saw a small dark shape bobbing off in the distance. I wiped my eyes and looked again—it was coming toward us. ‘Another boat!’ I cried out, overjoyed, thinking we would be rescued after all. Grandpa braced himself against the side of the hull and stood up, waving his arms and yelling as loud as he could. I grabbed on to his feet to keep him from toppling overboard, and together we waited to be saved.

“But as we watched, we realized that the thing approaching us was not a boat after all. I blinked and squinted, not wanting to believe my eyes, hoping that the rain was blurring my vision. Grandpa stopped waving and went silent, his face puzzled at first, then terrified.

“It was a man, not a boat. He was walking upright over the water—I swear it on my mother’s dirt grave in Ha Tinh—staggering across the sea as if it was just unruly land. Perhaps I cannot say that it was a man, for it was clear that he was long dead, and from the looks of it had met his end by drowning; the body was bloated and the flesh that hadn’t already been eaten by fishes was a terrible greenish-black color. The chest had been torn wide open, and I could see ribbons of kelp threaded among the white bones of its rib cage. Whatever spirit had reanimated the corpse must have been a feeble one, for the body moved clumsily, legs stiff but head dangling loose as it struggled to keep its balance on the angry waves. Grandpa sank down to his knees next to me, and we peered over the gunwale in helpless horror as the body tottered closer and closer.

“When there were only a few feet of churning black ocean left between it and our boat, the corpse stopped. It swayed before us like a drunk man—and for some reason it stood on tiptoe, the decomposing feet arched like a dancer’s—dipping and rising with us on each wave but never breaking the skin of the water.

“Grandpa and I waited for the body to move. To talk. To pounce on us. But it simply stood there. I felt it was watching us even though its eye sockets were empty—for the face is where the fish nibble first, you know. We crouched in the boat until our knees hurt, all the while under the sightless gaze of this unnatural thing. Grandpa would have vomited in fright had his stomach not already been empty from throwing up all night. Eventually I couldn’t take it anymore; if I was going to die, I wanted to get it over with.

“ ‘Spirit!’ I called out, my voice so small against the storm. ‘What is it that you want?’

“The drowned man’s head flopped down to one side and it turned its rotting palms out to me, as if to show that it didn’t know, either.

“ ‘My husband and I have nothing to give you; no rice or incense to make an offering with. We do not know how to lay you to rest.’ A wave slopped over the side of the boat and I received a mouthful of salt water. I spat it out and continued. ‘We are just two wet and weary souls, like you.’

“I didn’t have to shout these last words, for the wind had begun to quiet down. The rain was no longer beating on my skull and the back of my neck.

“With the jerky movements of a puppet on strings, the corpse lifted its head once more and bent its knees. It had no eyes, no lips or cheeks, and there was only a little bony ridge where the nose had been, yet it still looked sad. Poor thing: lost, half-eaten, and a little too alive to be completely dead. It spun on its tiptoes, then began wandering away across the waves once more. Grandpa thought it went south, and I was sure it went west, though we were probably both wrong, for we were still dazed by the storm. It did not turn to look back at us, and after a while we couldn’t see it any longer.

“The waves were far from calm and the sky too dark for us to be optimistic, but Grandpa began steering us toward what we hoped was the shore. When we finally made it back to land we were shaking, but not for the reasons you might think. It wasn’t that thing we had met out on the water that frightened us, but the fact that we had gotten away so easily. Because what we suspected then was that there would be a price to pay later. I look at it this way: On that stormy day the spirits did not take us, but they wrote our names down in their book, and we knew they would eventually come collecting.”

“GRANDMA! WHAT THE HELL was that?”

“Watch your mouth, con.”

“Seriously, if Mom heard you talking like that, she’d think you were losing it and send you right to an old folks’ home!”

“Well, now you know why I never tell your mother any of my stories.”

“What am I supposed to do with a story like that? I’m going to fail history! And your papaya is giving me a stomachache!”

“Con, if you were listening you would have learned almost everything you need to know about your history. The first rule of the country we come from is that it always gives you what you ask for, but never exactly what you want.”

“But I want the real story!”

“That was a real story. All of my stories are real.”

“No! You know what I mean, I know you do! Why can’t you tell me how you escaped?”

“It’s simple, child: Did we ever really escape?”

THE FRANGIPANI HOTEL

THE ONLY PHOTOGRAPH I have of my father doesn’t show his face. He and his two brothers stand with their backs to the camera before their father’s grave on a sunny day in April 1973. My grandfather was killed when a building collapsed during the bombings that December, and the incense on top of his tomb—just visible over my uncle’s right shoulder—is almost all burned down. All three of the brothers are wearing their traditional silk jackets and trousers, but the trousers are white and don’t show up well because of the brightness of the sun and the pale marble of the cemetery all around them. It tricks my eyes whenever I look at it—for a moment I always think they are floating.

The picture hangs in the lobby of the hotel now, on the wall before you reach the stairs, and like everything else in the building, it’s covered in a film of perma-grime. My family has owned the Frangipani Hotel on the corner of Hàng Bạc and Hàng Bè since the thirties, when it was L’Hôtel Frangipane. Swanky name, shitty place. It’s in the Old Quarter, where all the buildings are narrow and crooked and falling apart, and some still have bullet holes from the sixties in their concrete sides. There’s a karaoke bar across the street, a massage parlor of ill-repute next door, and the Red River’s a couple of blocks east. The Frangi itself is a seven-story death trap, with four-footed things scurrying around inside the walls and tap water that runs brownish. If you slammed a door too hard the entire thing would collapse. It’s painted a sickly pale pink on the outside, and lined with peeling brown-and-gold–striped wallpaper on the inside. The large sign that hangs on the front of the whole mess with “The Frangipani Hotel” painted on it is crooked.

When Hanoi was bombed, the building was abandoned and five army officers and their concubines moved in. After the war, when what remained of our family began trickling back into the city, they found maps and diagrams scrawled in chalk on the walls and dusty boxes of ammo stacked in corners. I don’t know how they managed to get the place back—the government was still repossessing property and evicting people left and right in the postwar years. Maybe we were lucky. Maybe the place was even too old and nasty for the communists. I don’t know how we manage to stay in business now—Hanoi is full of newer hotels in less seamy parts of town, and why anyone would choose to stay at the Frangi instead is one of my favorite diverting mysteries to ponder while I’m working at this shithole.

I’m at the reception desk because I’m the only one who speaks passable English, and my cousins Thang and Loi are doormen or bellhops, depending on the situation. Thang is the good-looking one—high, chiseled cheekbones, long eyelashes, the kind of red-brown skin that looks warm and like it would smell slightly spicy, the kind of smile that makes women weak in the knees. Loi has the face and personality of a toad. However, he can be useful because his ubiquitous presence dissuades our female guests from trying to sleep with Thang, and because he makes even me seem handsome by comparison.

Their father—my uncle Hung—is legally the owner and manager of the hotel. He and my father and their brother Hai ran it together before the war, but then Uncle Hai drowned in an accident that no one ever talks about and my Ba went insane and offed himself a few years later, so now it’s his. In his mind, Uncle Hung is a major player in what he refers to as the “Hospitality Industry,” and not in charge of a half-star hotel. He’s even started calling himself “Mr. Henry” in an attempt to better connect with the Western guests. However, he can’t really pronounce “Henry,” let alone “Frangipani,” so watching him greet guests and introduce himself is endlessly amusing.

The other day, Mr. Henry decided to assemble the family for what he called a “staff meeting.” It consisted of him, Thang a

nd Loi, their mother and her sister, who are the housekeepers, me, my mother, who cooks the complimentary breakfasts, and my grandmother—my Ba Noi—who either sits upstairs in her room and raves all day or is dragged downstairs by Mr. Henry and positioned in the lobby with a cup of tea to give the hotel a homey feel.

We gathered in the first-floor room where Thang takes his girls and Loi and I take naps on slow days.

“Why are we here? What are we doing here?” Ba Noi said as she sat down.

“I agree,” said my auntie Linh. “Why do we need a meeting, Hung? Couldn’t whatever it is have waited a couple of hours until dinner?”

“I think Ba Noi is just being generally senile,” I chimed in. “She probably doesn’t even know we’re having a meeting.”

Thang and Loi at the same time: “You’re a little shit, Phi, you know that? A real shit,” and “Don’t talk about Ba Noi when she’s in the room!”

I looked over at Ba Noi. She was smiling beatifically at a decorative vase of plastic flowers. Mr. Henry—who was wearing only boxer shorts and rubber sandals to his own staff meeting—tried calling everyone to attention. He cleared his throat.

“Valued employees!” he began. He had obviously rehearsed this beforehand. My auntie Mai turned her snort of laughter into a cough when he shot her a look. “Valued employees, I have called this meeting because I have decided that we must change our entire marketing strategy …”

I hadn’t realized we’d had a strategy, other than not to accidentally poison the guests, or, in Thang’s case, accidentally get them pregnant.

“… We need to add a little more class to our establishment …”

Uh-oh. The last time Mr. Henry wanted to add more class to the Frangi, he sank us into debt by installing a heinous plaster tiered-basin fountain in the middle of the lobby that breaks down every month or so.

“… And we need to reach out to the international corporate community! It’s the businessmen from Japan and Australia and Singapore and the USA who have all the money, and so we will convince them to come to the Frangipani Hotel! How will we do this?” Mr. Henry paused dramatically to stare around the room at us. “Easy!” He dragged a large plastic shopping bag from the closet and began to dole out its contents. With his drooping stomach, he looked like a budget Vietnamese Santa Claus. First he pulled out a large stack of looseleaf paper and handed it to Auntie Linh.

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction