- Home

- Violet Kupersmith

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction Page 13

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction Read online

Page 13

“Unf,” he said. He hauled himself out of bed, then shed his pants and underwear and walked naked to the shower. Mia gathered his discarded clothes, which reeked of smoke and alcohol, deposited them in the laundry basket, and went to start the coffee and make Charlie’s sandwich. As soon as she stepped into the kitchen, she froze.

The window was open. The latch was dangling unfastened; balmy morning air permeated the apartment. Mia dashed across the room and slammed the window shut. She locked it, jiggled the latch to see if it was loose, and when it wasn’t, she finally exhaled. But a few seconds later, her breath caught in her throat once more when she saw that the windowsill was covered in long, deep scratches. In order to make marks like that, the cat must have clawed the wood relentlessly, over and over. Horrified, Mia backed away from the window just as Charlie entered the kitchen wrapped in a towel, scrubbed and rosy and battling an imperial hangover.

He made a sound that was halfway between a groan and a grunt, and reached around Mia to get a glass of water.

Mia repositioned herself so that Charlie was between her and the window. “How was the rest of the night?” she asked brightly as she began messing about with the lunch fixings, and hoped he couldn’t see her hands shaking.

Charlie shrugged and said something else in Neanderthal.

“Did you have a good time with Barry? I’m so disappointed that you’ve never introduced us before.” Mia slathered mustard viciously on a slice of bread. “We had such fun talking together. She’s quite the sparkling conversationalist. A real wit. An—”

“Don’t do that.” Charlie had regained his use of language. “It’s so ugly. And Barry’s a riot when you actually try and get to know her.”

But Mia couldn’t stop herself. “I’m sure I’ll learn what a riot she is in another nine months when she and little Neil Junior show up at my office. No, wait, I guess she’d have to go over to the Canadian Consulate, wouldn’t she?”

Charlie finished drinking his water and placed the glass down carefully on the counter. “I don’t know why you’re like this,” he said. His voice was so deliciously cold. Mia shivered. “You chose to live here, did you forget that? No one forced you to come work in this country. No one held a gun up to your head and told you to stay. Why are you even in Vietnam? You hate your job. You don’t have any compassion for the people here. When was the last time you actually talked to a local person who wasn’t selling you something?”

Mia threw her knife into the sink, which was still full of dirty dishwater; then, as an afterthought, threw in the slice of mustard-covered bread, too. “Make your own sandwich,” she said.

“I never asked you to make my fucking sandwiches for me,” spat Charlie. “Not once. I never asked you to pick out my clothes. I never wanted you to pretend to be a—to be my wife. God, for someone who hates Vietnamese women, you’re just like one.”

“No,” said Mia. “They fuck you because they think they’ll get a green card out of it. I do it just because I couldn’t find anyone better here.” With that she turned, left the kitchen, and locked herself in the bathroom. Charlie left the apartment ten minutes later—Mia heard the front door click shut—but she stayed in there an extra five minutes, just in case he had forgotten something and had to come back. She searched the apartment for her phone, eventually finding it on the floor next to her discarded heels. Mia retreated to the bathroom once more, where she perched on the toilet seat and carefully dialed the numbers written at the top of the receipt she had removed from her jewelry box.

She emerged a few minutes later with the receipt still in her hand, but now scrawled across it in brown eyeliner was: “118B Nguyen Thai Binh, Tan Binh, 9:30.” Mia paused as she passed the bedroom. The shirt and tie and trousers she had picked out for Charlie were still arranged on top of the covers, untouched, but his outfit from the night before was missing from the hamper now. Mia walked over to the bed and stretched out alongside the empty clothes. It looked like she was lying next to an invisible man. She snuggled closer and rested her cheek on the breast pocket of the button-up.

“I’m sorry,” she breathed. She reached across the shirt to hold its cuff in her hand and listened for a heartbeat beneath the fabric, even though she knew there wouldn’t be one.

TWO HOURS LATER, Mia flagged down a taxi and showed the driver the receipt with the address Tuan had given her. The car slipped into the current of morning traffic on Dien Bien Phu, parting the motorbikes like a hand through a swarm of gnats. Mia rested her head against the window and watched the hot sun cooking the various surfaces of the city: tin roofs, asphalt, brown skin.

Outside District 1 there were fewer trees, but tangled power lines hung low across the roads like jungle creepers. The buildings were all skinny and pale yellow, their balconies crowded with strings of drying laundry and red flowers growing in planters made from repurposed water jugs. The taxi’s air-conditioning was at full blast; for the first time in ages, Mia felt chilly. She wondered if Tuan would be like Charlie’s girls, and expect her to marry him once they had slept together.

Maybe she would, Mia thought to herself, her mind feverish. She would buy a traditional dress and marry Tuan in an incense-choked ceremony. They would rent a one-room apartment in one of these butter-colored buildings. She, too, would hang their laundry out on the balcony and grow red flowers. Her parents would come to see her in Vietnam, her father would give Tuan dirty looks the entire time, and her mother would cry when she saw the rats and the stray dogs and the children running around without pants and the toothless old men holding rooster fights in the street. Mia would have a baby and fill out the paperwork for its American citizenship herself.

The hotel at 118B Nguyen Thai Binh that the taxi pulled up in front of was named—uncreatively—“Hotel.” Underneath its sign was another sign, but in Japanese; beneath that was yet another in Korean; and beneath that, Tuan was waiting for her on the sidewalk. He was parked on the same yellow motorbike he had been fixing the day before and which, Mia gathered, was now fully functioning. Mia had never seen him wear a shirt before. A handful of depressed-looking Asian men in suits were milling about in the lobby; the neighborhood they were in seemed to cater to foreign businessmen. Mia liked that she was among outsiders. She began counting out the bills for the driver but paused when, for the first time that morning, she noticed the state of her fingers.

The nails on her right hand were all ragged and ground down. Mia brought them closer to her face; her gold polish was almost all worn away, and her fingertips were rubbed raw. The driver coughed impatiently, so Mia paid quickly and got out of the taxi. She curled her fingers into a fist to hide them.

“My Mia,” said Tuan, rising from the motorbike. “I know you will come to me.” He held his hand out to her and she took it. Together they entered the cavernous lobby and received a key and a knowing smile from the boy behind the reception desk.

Their fourth-floor room had naked wires sticking out of the wall and heavy dark curtains. A previous guest had left two books behind on the nightstand but the spines were turned away from Mia and she couldn’t read the titles. There was no air-conditioning or fan, but for some biological reason Tuan was not sweating the way Mia was. She didn’t mind being hot now—it made the decision to take her clothes off easier. While Tuan was locking the door, his back to her, she peeled off her jeans and shirt and left them in a pile on the floor. “You have a condom, right?” she asked.

“I do not know what it is,” said Tuan, before turning from the door to her. Immediately, he looked aghast. “Mia! What is wrong with you?!” he cried.

This was not the reaction she had hoped for. Mia looked down at her body. “You don’t think I’m beautiful?” she asked, hurt. It was impossible that he didn’t. For one insane, brief moment, Mia imagined that Tuan was somehow able to see into her mind, into her heart, and that his horror had been in response to seeing all the ugliness that was there beneath the skin, gnawing a hole somewhere deep and vital inside her.

“What? No! Mia, what is wrong with this?” Tuan was gesturing at the thick layers of gauze Mia had dressed her burn with.

Mia felt embarrassed. “A motorbike.” She sat down on the edge of the bed.

Tuan knelt next to her and began unwrapping the bandages on her leg. When he saw the wound he was relieved. “It is not big,” he said. “Not bad. Just like a little kiss. But you cannot hide under this, okay?” He waved the gauze pads at her. “If you hide, it will become like mine.” He rolled up a sleeve to show her a cluster of small brown scars around his elbow. Mia was skeptical of this medical advice but said nothing. Tuan sat next to her on the bed. “Now,” he said with a smile, “what is wrong with this?” He brushed the wetness on Mia’s cheeks with the back of his hand.

Mia hadn’t realized that she was crying. She wiped the tears away; they stung her fingertips. “I have a boyfriend, Tuan.”

“It is okay. I have a wife.”

“What?!” Mia scooted away from him on the bed, toward the headboard.

“Mia. My Mia. I will explain. Listen to me. I have a wife but we do not have a wedding yet. She lives in my village. My father and mother, and the father and mother of my wife—they are friends. When my wife and I are both little, they make a promise that we will have a wedding someday. Do you understand?”

“An arranged marriage?” Mia was appalled.

He shrugged. “It is business.” He shifted on the bed so that he was next to her again.

“What is she like?” asked Mia.

Tuan chewed his lip while he thought. “She is not tall. Her feet are big. She likes cooking. She kills a fish with a knife so quickly. Not the, the …” He struggled for a second to remember the word. “Not with sharper part. Like this—” Tuan grabbed Mia’s hand and began smacking it with his palm. She presumed that her hand was the fish and that his betrothed spanked it to death with the side of the knife. Tuan was getting excited now; the good part was coming. “Then…WHA!” He brought the blade of his hand-knife down on her dead hand-fish. “Head is gone! And ch ch ch ch ch,” he took the scales off with little flicks of the wrist, even turning it over to make sure both sides were cleaned. His eyes narrowed for a moment when he saw Mia’s wrecked nails.

“Tell me more,” Mia said, pulling her hand away from him.

“My wife does not know how to swim. She is scared of ghosts. She has hair to … here.” Tuan placed his hand on Mia’s hip to indicate the length and did not remove it when he continued. “She does not speak English but she likes songs from America. When she sings she does not know the words. The drink she likes most is sugarcane juice. When she drives a motorbike it is too fast.” He began unbuckling his pants with his free hand. “She is a good daughter. She loves her mother and her father.”

“Does she love you?”

“Yes,” said Tuan, as he covered Mia’s body with his. “And I am sorry.”

CHARLIE CALLED THE DAY before Mia left, asking if he could come over to say goodbye and help her pack, which was kind. Mia hadn’t expected to see him again. All she’d heard from one of their old mutual acquaintances was that he was living in a little place in District 2 now; when Charlie went away he took all his friends with him. However, he had accidentally left behind Broken-Ear Uncle Ho when he moved out, which Mia thought might partially account for his interest in visiting her.

By the time he got there she had already finished packing; of the five suitcases that Mia had arrived with, only two were leaving Vietnam. She had piled up all the items that weren’t coming back with her in the living room like a messy altar—the three discarded suitcases at the bottom, then the laundry basket with most of her clothes; toothpaste and half-empty shampoo bottles and other toiletries that she would replace in America; cups and plates, forks and frying pans; the expensive coffeemaker; and resting serenely atop it all, Uncle Ho’s head, wearing the motorbike helmet that Mia hadn’t used since Charlie had gone. Her entire collection of high-heeled shoes was littered around the base, all of the soles blackened and scuffed.

Charlie eyed the pile keenly. “Feel free to scavenge,” Mia told him. He must have come straight from class; he had his work satchel with him and his necktie was stuffed into his pocket. They sat on the couch and wondered what to say to each other. Mia chewed on a fingernail absently. Charlie had goose bumps on his forearms because the air-conditioning was cranked all the way up.

“You’re not bringing back much, huh?” he eventually said, breaking the silence. “Just two bags?”

Mia smiled. “And two carry-ons. But they’re very, very small.” Just one coin-sized scar on her leg, and one pea-sized embryo in her uterus.

“That’s good,” Charlie said, rubbing his cold arms.

At the Western clinic the doctor had told her it would look like a little tadpole at this stage, which made Mia think of Tuan’s eyes. She had imagined them growing inside her and burst out laughing, and the doctor had given her a funny look. He was a white-haired British man who had come to Vietnam as a specialist in obscure tropical diseases but been forced to switch fields because of the demand in what he called the “field of family planning.” Mia found this amusing, too, considering that neither of their plans had worked out as intended. The small pack of white pills he had given her was still unopened; she had wrapped it up in four old receipts and stowed it in her jewelry box, which was now packed inside one of the suitcases.

Charlie studied Mia’s face as if he were trying to memorize it. “Will you miss this place at all?” he asked.

Mia did not answer. She stood up and retrieved Broken-Ear Uncle Ho from the pile of abandoned possessions, holding it tenderly in her arms for a moment before laying it on Charlie’s lap. “I’ll walk with you to your motorbike,” she said.

She didn’t know which one was the father. In her mind the child would have Tuan’s broad nose, his tan skin, his generous lips, and the narrow shape of his eyes, but their color would be the green-blue of Charlie’s and its cheeks would bear the faintest trace of freckles. Its soft hair would curl at the ends and possess all of the ten thousand shades between black and brown. Charlie and Mia left her apartment and walked down the stairs side by side. Their hands grazed once. Perhaps neither of them was the father of her child, Mia thought to herself. Perhaps it was the city itself that had spawned it.

While Charlie was tucking Uncle Ho into his satchel, something tumbled out of the bag and fell onto the sidewalk between his motorbike and the wall of the building.

“Let me get it,” said Mia, reaching behind the rear wheel. She didn’t see the look of panic that crossed Charlie’s face. “I think I can … Oh!” Her hand had closed around a high heel. When she pulled it out she saw that it was the left shoe of her pair of peach-colored stiletto sandals. There were still indentations worn into the footbed where her toes had once been. “Are you giving these to someone?” Mia asked. “I’m not angry—you can take all of them.”

“No! I mean, that’s not why I … I wasn’t …” Charlie stammered. He was blushing. “It’s not for anyone but me. Look”—he held his satchel open—“I only took one. I slipped it into my bag when you weren’t looking so I wouldn’t … because I still …” His voice broke off when he saw that Mia was beaming at him, and then he smiled, too. They stood facing each other on the sidewalk, smiling like fools, glowing in the sunlight, and for one last time they were a couple again and the chaos of the city that surrounded them didn’t exist.

“Charlie, I’m—”

But Charlie would never know what she meant to tell him, because a familiar, high-pitched feline wail rose up suddenly from the trash cans on the corner. The cat, which hadn’t shown its face in weeks, had returned. Charlie and Mia turned their heads as one of the bins toppled over with a crash and the raggedy tabby crawled out. One of its legs was still gimpy and it looked as if it could barely support its bloated torso. The cat lurched toward them, mewing tremulously and shedding bits of garbage and tufts of its own fur. Mia’s fingers tightened around th

e shoe in her hand.

“You!” As she uttered the word she hurled her sandal at the creature as hard as she could. It gave a final yowl as the heel clipped its side and then ran into the street, where it was immediately crushed under the wheels of a passing taxi.

Charlie’s face was horrified. Mia’s was jubilant. Seconds passed. The taxi was long gone—it hadn’t even slowed down when it hit the cat.

“Poor thing,” said Charlie. Mia reached for his hand but he had already stepped into the street, ignoring the traffic that swarmed around him. She followed even though she didn’t need to look.

It wasn’t as grisly as she thought it would be. Only the head had been squashed under the tires, and there was barely any blood.

“Goodbye, little cat,” said Charlie quietly, bending over the carcass. “I’m so sorry.”

But I’m not, thought Mia. You brought this upon yourself, ugly thing. What did you want from me?

“God, look how swollen its belly is.”

Did you want food?

“Full of parasites, probably.”

Did you want to be loved?

“No, not parasites,” Charlie said, bringing his face closer. He ran one finger lightly over the curve of the animal’s stomach, but it was Mia who shuddered. “I think it—she—was pregnant.”

TURNING BACK

THOUGH ONE FORTUNATE consequence of my father’s disappearance was that we became estranged from his family and whatever nuptials they might incur, given the size of Momma’s side there are still at least four weddings to attend each year. Weddings of cousins, weddings of second cousins, weddings of people who are most likely cousins because their last name is Nguyen and they live within a sixty-mile radius. When our family tree was transplanted here from the charred soil of South Vietnam in 1975, it began sprouting with wild abandon; as a result I am now probably related to a third of the greater Houston area by either blood or marriage.

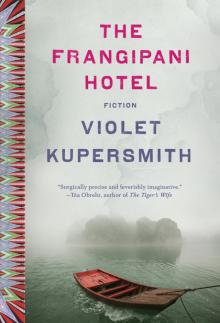

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction