- Home

- Violet Kupersmith

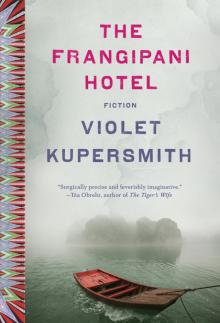

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction Page 19

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction Read online

Page 19

“Mẹ? Mẹ? Mom? Are you there?”

At the sound of Lam’s voice, the tank disappeared. Not instantly, as it had appeared, but in pieces, like a puzzle disassembling: The muddy wheels vanished first, and then the hull, leaving the gun hanging in the air by itself. Then Ms. Nguyen blinked, and it too was gone. She tightened her hold on her telephone with one hand and gripped the edges of the stiff, upholstered armchair with the other, anchoring herself in the physical world. When she spoke her voice was steady: “Yes. I am sorry; I am losing my attention so easily these days.”

Though Lam said nothing, her mother could hear her shifting uncomfortably in her chair on the other side of the line. Ms. Nguyen smiled and continued: “The shaking came back today, con, so the nurse had to dial your number for me. And I have new pains in my knees. I ate lunch with Mrs. Phillips and she thinks that my cough is becoming worse.”

Lam exhaled and said, “Mẹ, I—”

Ms. Nguyen continued as if she could not hear her daughter: “But don’t worry yourself about me; I am sure that a little rest will take care of everything. That’s all I need. A little rest. I haven’t been sleeping well, you know. Sometimes I lie awake all night.”

“Mom!” Lam’s voice was shrill and pleading. “There’s something I need to tell you.”

“I am always listening, con.”

“I can’t fly down for Lunar New Year like we planned.”

Ms. Nguyen was silent. She could tell that her daughter was choosing her words very carefully.

“Plane tickets aren’t cheap, Mom, and it’s going to be a bad week at work. I really can’t take off. I’m sorry, Mẹ.”

Ms. Nguyen pressed her lips together tighter.

“Please, Mom, I just saw you over Christmas, and I’m flying down for Easter, so I’ll see you soon. I just can’t for tt.”

“Oh, con,” Ms. Nguyen said at last. “Did you know, my feet are always cold now?”

Lam sighed. “Then you should wear the wool socks that I sent you, Mẹ.”

“They are very slippery, con.”

After she hung up the phone, Ms. Nguyen stood and walked slowly and deliberately around the entire room before sitting down again. She realized that she was probably losing her mind, and felt a little shiver of delight.

UNLIKE THE OTHER WOMEN in the St. Ignatius Assisted Living Facility, Ms. Nguyen never mourned for her lost past. Her fellow residents still longed for the 1950s and ’60s, when they were wasp-waisted Houston housewives. Those were sun-drenched days: clean, ruddy-cheeked children climbing the live oak trees and pecan pies cooling on windowsills. The world was different now—these women had become little more than swollen-heeled bags of bones—but they still dyed their limp hair biweekly and daubed dark eye shadow onto wrinkled lids for dinner in the cafeteria or for bingo night. They kept their old dresses in their closets: slinky gowns cut in velvet and satin that smelled like cigarette smoke and old oil money. They turned their dressers into shrines, covering them with black-and-white photographs of their younger, smiling selves.

Unlike them, Ms. Nguyen did not court memory. She was relatively young for a resident but as wizened as the best of them, and wore her wrinkles, her liver spots, and the stoop in her back with something like grace. Looking at her it was impossible to envision the young girl that she must have once been. But Ms. Nguyen had her ghosts. She had tried to leave them on the other side of the Pacific, but they had followed her at a distance, never quite letting her out of their sight. And now that she lived at St. Ignatius, where she spent the long days in an easy chair, watching the hours limp slowly by, they were becoming harder to ignore. The mind drifted away too easily here; the walls were all bare and cream-colored, and in this blankness the memories crept in. They lapped at the edge of her consciousness like the Mekong, deep and patient and full of silt, and soaked into her dreams. There were good ghosts—the breeze that made the rice stalks dance, the snort of her father’s water buffalo, the way the sunlight would make a halo on her mother’s black hair—but there were many more bad ones: the shrieking sound of exploding shells in the night, the dried blood in the street gutters, the hissing sound of a soldier’s fly unzipping, his shadow obscuring a figure curled on her side on the ground…

Ms. Nguyen had not feared the tank. But because it had found its way into this world, materializing in front of her in broad daylight, she feared that the other ghosts would soon follow.

She spent the time before dinner in a state of extreme alertness, wondering if she would see it again. While she waited, she examined in minute detail the state of her cracked, yellowed fingernails and the pattern of blue veins that rose in ridges on the backs of her hands. She imagined that she could feel things shifting and creaking underneath her skin. At five thirty she rose from her chair and left her room, noting with satisfaction the various clicks and groans her body made as it slowly settled into an upright position. She viewed each new pain, each new corporeal malfunction that indicated another teetering step down the path of senility, with a twisted joy. Her first hot flash had been more exciting to her than her first period, and she was anticipating the day when she would get a cane. In the mornings when she dressed herself she would sometimes catch a glimpse of her own hunched back in the mirror and smile. As she made her way toward the elevator, she calculated in her head the time difference between America and Vietnam. It was very early in the morning there. When she passed the front staircase on her way down the hallway, she let one hand rest briefly on the carved rail of the banister. To her, the stairs were more alive than anything else in this place.

St. Ignatius was a square, ugly concrete building, colored in chromes and dirty pinks and teals and linoleum marked gray from skidding wheelchairs, but the front staircase was its one feature of aesthetic note—it was a relic from some earlier, lovelier time, high and curving and made from a dark, lustrous sort of wood. It was mostly for show; nearly all of the residents relied solely on the elevator to move from floor to floor. Had the facility been larger, or wealthier, the staircase would have been declared a safety hazard and consequently remodeled and fitted with handrails, wheelchair lifts, and emergency buttons. But St. Ignatius—much like the residents it housed—was forgotten and falling apart, and no safety inspectors came, and the tall staircase, with its naked, uneven wood, remained.

For the residents who could still chew, dinner was corn bread, okra, a flabby turkey cutlet, and an unnaturally yellow slice of lemon meringue pie. Things were still, save for the chomping of fifty pairs of elderly teeth and the ceiling fan shuffling around the stale air. Alone at her table, Ms. Nguyen ate slowly. She still had all her teeth, but they would probably be gone in a couple of years, she reasoned.

Sometimes she liked to talk to herself while she ate. But unlike the residents who yelled obscenities at invisible beings, heard voices, and drooled uncontrollably, when Ms. Nguyen held her mad conversations with herself they were always calm, polite, and in Vietnamese, which seemed to disturb the nursing staff even more.

“I’ve heard about people going back, as tourists,” she was saying that evening, holding her fork up to the light so that the tines reflected it. “To Vietnam, I mean. Back to the motherland. But how can they stand it now that everything is changed?” She paused, then nodded as if receiving a response. “I would only go back to see Ha Long Bay again. Ha Long has been the same for centuries; it will be the same for centuries to come. Have I ever told you the story of Ha Long?” She waited again. “No? I used to tell it to Lam, when she was a child. You see, long ago, a dragon fell from the sky. It broke the ground where it landed, broke it into a thousand islands. When it—”

She was interrupted by a commotion by the doors. Mrs. Gaston, a hefty woman of seventy-five, who, last week, had tripped over her own walker and fractured a metatarsal, was entering the cafeteria with her foot in a cast, pushed in a wheelchair by her son and followed by a parade of grandchildren. Ms. Nguyen’s initial displeasure at the disruption suddenly disappeared�

�she had an idea. She did not say another word for the remainder of dinner, and all the nurses breathed a sigh of relief.

EARLY THE NEXT MORNING, as the sun rose, Ms. Nguyen stood at the top of the stairs wearing her pajamas and the pair of thick, gray woollen socks that had been a present from Lam. She wriggled her toes inside them; for the first time in a long while, her feet felt warm. Ms. Nguyen swayed a little, feeling the surface slide beneath her socks. It tickled slightly. She needed the correct kind of accident—the hip, ideally, or the ankle. A wrist might not be adequate. She swayed again, more intensely. Perhaps the staircase wasn’t steep enough. But she knew she had to act soon—the cleaning ladies would be arriving within the hour. She was not afraid.

Ms. Nguyen bent her knees and felt short of breath. Sunlight was crawling through the windows, turning the world white again. She let go of the banister. The old ghosts were flooding in, and Ms. Nguyen realized as she leapt that she was falling into their waiting arms. In the space of time between her toes leaving the landing and her body crumpling as it hit the floor at the bottom, she looked through the front window and saw that the tank was back, planted triumphantly in the middle of the lawn, glowing reddish in the early morning sun. It did not belong here, but neither did she.

Ms. Nguyen lay sprawled on her left side, with her leg bent at a strange new angle beneath her. She decided that it might be a good idea to begin yelling but discovered that her mouth was already open; tears were on her face, and people were running toward her. She heard herself making loud, animal yelps, and the sound surprised her. But by the time the medic came, Ms. Nguyen had calmed herself down enough to inquire when her daughter would be arriving.

To Peter, Mai, and Allan

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

FOR THEIR SUPPORT, patience, and guidance, my deepest gratitude goes to: Cindy Spiegel, Molly Friedrich, Lucy Carson, and Molly Schulman; Don Weber and the sage members of the Mount Holyoke College English Department; the Pham, the Block, and the Kupersmith clans; and the friends scattered from Yorkshire Road to South Hadley, from London to the Mekong Delta.

And to Valerie Martin, for everything.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

VIOLET KUPERSMITH was born in rural Pennsylvania in 1989 and grew up outside of Philadelphia. Her father is American and her mother is a former boat refugee from Vietnam. After graduating from Mount Holyoke College, Kupersmith received a yearlong Fulbright Fellowship to teach and research in the Mekong Delta. She is currently at work on her first novel.

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction