- Home

- Violet Kupersmith

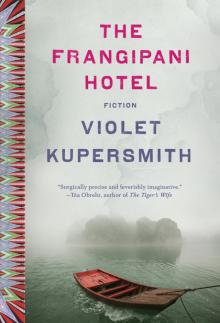

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction Page 5

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction Read online

Page 5

“Why won’t he?”

She steps delicately into the lake. I jump in after her. It is much shallower than I expected. “Why won’t he?” I ask again, more urgently. “Answer me!” Her black and silver dress is turning into moonlit ripples on the water, and her hands are covered in scales. She turns and gives me a triumphant smile, or maybe she is just baring her teeth.

“Oh, Phi,” she says. “You’ve broken your promise.”

I stop with my shirt still dry. She slips away until only her head is still visible.

“Why not me?” I whisper to the lake because I have already lost.

“How funny,” she says before vanishing beneath the surface. “Your father asked the very same thing!”

And I find myself alone, standing waist-deep in the water.

SKIN AND BONES

MRS. TRAN HAD BEEN CONSIDERING it for a long time, but she made up her mind for certain when she found her younger daughter Thuy in the kitchen, crouched like an animal in front of the open refrigerator, ripping off chunks of a leftover chocolate cake with her bare hands and devouring it. Calmly, Mrs. Tran took the cake from Thuy’s hands, lowered it into the trash can, then went and made one of her rare ten-cents-a-minute calls to Grandma Tran in Vietnam to make the arrangements. That very day she booked both of her girls round-trip tickets—Houston to Ho Chi Minh City, twenty hours with a three-hour layover in Seoul—leaving that very weekend and returning at the end of the summer holidays three weeks later. Thuy and Kieu’s father, who lived with his new wife and children in Atlanta, paid for the plane tickets because he owed the girls birthday presents. Mrs. Tran told Thuy and Kieu that the trip was a chance for them to rediscover their roots, but Thuy knew the real reason: Her mother was sending her away in the hope that she would lose fifteen pounds on a diet of fish and rice, maybe even more if she could catch a bug from the street food or dirty ice. Vietnam was Fat Camp.

Kieu complained at first. She wasn’t like Thuy—she had friends and boys waiting to flirt with her and pool parties to attend in spangled bikinis. Their mother, however, was unyielding; Thuy couldn’t possibly go alone. Mrs. Tran would go herself but she couldn’t take all that time off work. Besides, Grandma Tran wanted to see both of her grandchildren—she was getting on in years and wouldn’t live forever.

Thuy also suspected that her older sister—the skinny sibling, her mother’s accomplice in everything—was being sent along to monitor everything that Thuy ate. Kieu was an obedient calorie snitch, always quick to notice if there were potato chip crumbs on Thuy’s shirt or incriminating spoon marks in the tub of ice cream, but she was no match for Thuy, the junk food mastermind. As she packed her suitcase, Thuy planted several decoy chip bags near the top, hidden in an easy place for Kieu to find when she searched it later. Satisfied, her sister would overlook the box of cookies stashed near the underwear at the bottom, the chocolate bars in the toiletries bag, and the packets of cheesy snacks tucked carefully into each of Thuy’s sneakers.

The funny thing was that Kieu had once been the fat one. She had weighed almost ten pounds at birth and spent the first few years of her life as an immense, hairless Buddha of a baby. Thuy, born two years later and three weeks premature, had been scrawny in comparison. But over the years they had gradually switched places; Thuy ate her way to shapelessness while Kieu emerged from childhood slender as a rice stalk. Their mother didn’t bother correcting visitors who saw their baby pictures framed on the wall and automatically mistook Baby Kieu for Baby Thuy. Mrs. Tran, who hovered just shy of five feet and had never weighed over a hundred pounds in her life, often speculated about how she had produced daughters capable of such corpulence. Guiltily, she wondered if Kieu’s infant weight and Thuy’s current state were her body’s deferred response to the weeks in her own youth that she had spent starving, bobbing in a refugee boat on the South China Sea. Perhaps she had genetically tried to provide her offspring with some extra padding should the same fate befall them.

The night before their departure, Mrs. Tran snuck extra Pepto-Bismol tablets, mosquito repellent, and bottles of hand sanitizer into Thuy’s and Kieu’s backpacks. She gave them a piece of paper listing the addresses and telephone numbers of all their relatives, and another with Vietnamese phrases and their English translations to memorize, which she handed over with a lament that she had not taught them more of their mother tongue. Thuy glanced down at the sheet: “Please help!” “How much does it cost?” “I’m lost!” “Where is the bathroom?” “Call the police!” “Don’t touch me!” She gave them some money to give to Grandma Tran, some money to bribe the customs officers, and some money for themselves. Finally, nervously, she gave them a photograph of herself and their father as teenagers, standing in front of the Notre Dame of Saigon, both of them young and smiling and very, very thin. It was the first picture their mother had ever shown them from her old life in Vietnam.

“You should find this exact same spot and take a picture of yourselves there!” Mrs. Tran said. And then she surprised her daughters and herself by bursting into tears on the spot. Both Thuy and Kieu were unsure how to react to this rare display of emotion; Thuy looked down at her hands while Kieu awkwardly patted her mother’s arm. “I’m just going to miss you two so much,” said Mrs. Tran between snuffles. But somehow Thuy didn’t quite believe her.

ON THE AIRPLANE, Kieu had the aisle seat, Thuy had the middle, and an elderly Vietnamese man with a pencil mustache sat by the window.

“Going home?” he said to them in Vietnamese as they adjusted their seat belts, then in English when he realized they didn’t understand.

“Just visiting,” Kieu replied. Then, she added, “We’re going to Vietnam to rediscover our roots.”

“I’m going to rediscover my waistline,” Thuy muttered under her breath.

She was restless for the entire trip, the thought of the three weeks to come weighing heavy and gelatinous on her heart. The last time they had gone to visit their grandmother had been four years ago, and for only a week. Thuy had been eleven then, approaching chubby but not yet at a weight that alarmed her mother, and Kieu had been thirteen. Their mother came with them on that trip—her first time back in the country since she had left it in a fishing boat in 1975. She and Grandma Tran had spent every day peeling and eating fruit at the kitchen table, exchanging twenty-three years’ worth of gossip, while Kieu, who fancied herself a preserver of oral history, sat and listened to them talk even though she had no idea what they were saying. Thuy had just watched poorly dubbed Chinese soap operas in another room. When her mother went back to Vietnam again, two years after the first trip and two years before this one, Thuy and Kieu had stayed home.

IT TURNED OUT THAT they didn’t need the bribe money to get past customs—the officer was a pimply youth whose olive uniform was too big for him, and he was so distracted by Kieu’s low-cut blouse that he barely glanced at their paperwork before stamping it. The two sisters stepped, yawning, into the hot Saigon sunlight, where they waited on a curb for Grandma Tran to pick them up. There was a stall selling hot pork buns nearby—fat, fluffy things the size of a man’s fist—and Thuy’s mouth began to water.

“Give me some money,” she said to Kieu. “I want to buy a bánh bao.”

“Nope,” said Kieu nastily. “You’re shaped like a bánh bao already. The last thing you need is to eat more of them.”

Grandma Tran was nowhere in sight. The sidewalk was uncomfortably warm so both girls sat on top of their suitcases. Thuy hoped that her cookies weren’t squashed or melted. Kieu fanned herself with her passport. They sat on the side of the road and roasted in the sun for an hour and twenty minutes before deciding to take a taxi.

“WE! GO! HERE!” Kieu told the driver in loud, slow English. She handed him the sheet of paper with the list of relatives written on it in their mother’s even script, and pointed to their grandmother’s address at the top.

The taxi dropped them off early because the ngõ where their grandmother lived was far too narrow

and crowded for the car to drive down. Motorbikes clogged the road while skinny kids in cutoff shorts and dusty rubber sandals chased one another through the traffic; a fruit market took up half the street; men perched on plastic stools at every corner, gambling, the outlines of their ribs visible through white undershirts; old women, their flesh hanging from thin bones, emptied pails of foul-smelling liquid into gutters from their doorways.

Thuy and Kieu dragged their suitcases through the fray, stumbling over holes in the pavement and pausing frequently to brush sweaty strands of hair from their eyes. People stopped and watched their labored progress without bothering to hide their amusement. Several young children began to run in circles around the sisters like gnats, dispersing only after one of their mothers yelled something sharply at them from a balcony. After making it only a few blocks, the girls stopped so Thuy could catch her breath and Kieu could look up the house number. It was then that they discovered they had forgotten to get the paper with the address back from the taxi driver. Kieu said that it was Thuy’s fault, and Thuy was too hot and tired to disagree. However, they both had a vague idea of where their grandmother lived from their visit four years earlier. Thuy remembered that it was next door to a noodle shop, and Kieu was fairly sure that the building was yellow, with dark shutters. They found it five minutes later when Thuy caught a whiff of noodles and followed the scent to the correct block.

The house was smaller than they recollected; it was flanked by the noodle shop on one side and a modern-looking apartment building on the other, and was dwarfed by both. The shutters were closed, and the dark yellow paint was warped and peeling from the sun and the humidity. When Kieu knocked, the door swung inward almost immediately, but opened no farther than a couple of inches.

“Hello?” said Kieu.

A familiar crinkly face appeared in the space a moment later. “Allo!” Grandma Tran rasped, grinning with a mouth that was missing many of its teeth. She opened the door just wide enough to let the girls and their suitcases in, then closed it again once they were through. Grandma Tran only came up to Thuy’s and Kieu’s shoulders, so she stood on her tiptoes to give them each a kiss on both cheeks. She did not seem to realize that she had forgotten to pick them up at the airport, but the girls didn’t know enough Vietnamese to ask her about it. They removed their shoes—one of the few Asian traditions that they observed back home in Houston—and followed their grandmother down the hallway and into the kitchen, where dark stone tiles cooled the soles of their exhausted feet. The light was dim and vaguely pinkish; since their last visit, the window that looked out to the back garden had become almost completely obscured by a bougainvillea exploding with magenta blossoms.

Thuy noticed the smell as soon as she stepped inside but didn’t mention anything until Grandma Tran was busy getting them something to drink from a suspicious-looking pump in the yard. “What is that?” she whispered to Kieu.

“What’s what?”

“That smell.”

“What are you, some kind of bloodhound? I don’t smell anything.”

Thuy couldn’t describe the odor. It was subtle: a bit like the beach at low tide, a bit like the congealed goat’s blood stew her mother used to make, a bit like a too-ripe pineapple, and it seemed to emanate from the very walls of the house. It clung heavily to their grandmother, too, as she noticed when Grandma Tran returned bearing two glasses of water that tasted surprisingly clean.

As Thuy sat at the table and sipped her water in silence, the jet lag finally hit her. She found that her eyelids refused to stay open, her body ached from her toenails to the roots of her hair, and her chin kept dropping to her chest when she least expected it.

“You slip?” Grandma Tran asked them sharply, rousing Thuy. Thuy caught Kieu’s eye and saw that her sister was just as confused as she was. Their minds both worked at the same time to decipher the accented English: Slip? Sleep!

“YES! YES! WE ARE VE-RY SLEE-PY!” said Kieu in the same voice she had used with the taxi driver. But before Thuy could rest, Kieu insisted on letting their mother know that they had arrived safely. This turned out to be a messy and expensive ordeal involving miming things to their grandmother, three different phone cards, repeated dialing, lots of static, and yelling into the receiver. Grandma Tran didn’t even get to speak to her daughter because just as she took the phone from Thuy the line went dead.

The girls, too tired to lift their suitcases, dragged themselves to the spare room upstairs. They sank into the mattress in unison, and promptly fell asleep for sixteen hours. So ended their first day in Vietnam.

IT WAS KIEU, NOT THUY, who was ready to pack up and return to America from the start. “I can’t stand it!” the older sister said to the younger as they lay in bed on the fifth night. “I have no one to talk to—Grandma doesn’t understand English, and you never say anything! It’s like living in a house with two ghosts!” When Thuy didn’t bother replying, Kieu let out a frustrated little scream, pulled the sheet over her head, and complained to herself under the covers until she fell asleep. Thuy stayed awake for a while longer. She hated sharing a bed with her sister because Kieu had a habit of clinging to things in her sleep, and tended to grab Thuy’s belly fat, squeezing the flesh tightly with her bony little fingers all night long. Thuy found it odd that Kieu was so supportive of their mother’s war against her expanding waistline, because if Thuy were to actually lose the weight, her sister would have nothing to hold on to.

Thuy didn’t mind that she and her grandmother couldn’t speak to each other. In fact, she rather liked it, and found that their mutual lack of language skills freed them from the banalities of conversation. They had a routine now: Every morning, she, Kieu, and Grandma Tran took a walk around the neighborhood at a time when, at home, the girls would have still been in bed. They had been reluctant to venture outside since the circus of their arrival, but to Thuy’s amazement, no one paid her any heed; no one stared, no one laughed, no one looked at her at all. When she was with her grandmother, she was a local; she was invisible. Grandmother and granddaughters would shuffle down the street, turn right at the fruit market, and then walk until they reached the river, where they would stop to rest. In the soft morning sunlight, with the breeze off the water blowing back her gray hair, Grandma Tran always looked heartbreakingly young. She would clamber up on the lowest rung of the guardrail, her arthritic feet hanging out of the backs of her sandals, and lean over the edge, watching boats make their way toward the sea. At these moments, Thuy always wondered if Grandma Tran was thinking about her daughter in America. If she had known the words, she might have asked.

After a time, the sun would become stronger, causing little prickles of perspiration to start at the back of Thuy’s and Kieu’s necks—Grandma Tran, however, never seemed to sweat—and they would make their way back to the house.

Later in the day, when the heat was at its most vicious, a heavy drowsiness would steal over both Kieu and Thuy and they would take cots out on the balcony overlooking the backyard and nap. During this time, Grandma Tran napped, too, but she always stayed in her overgrown garden. Thuy, through drooping eyelids, could half-see her grandmother stretched out on her favorite patch of grass, her figure hazy in the sunlight, surrounded by lush vegetation and crooked fruit trees. She wasn’t sure why, but in these moments between waking and dreaming, the strange smell would become much stronger, assaulting Thuy’s senses with its cloying aroma. Each day, it was the last thing she remembered before falling asleep.

But by the time she woke up the smell had always abated, and she and Kieu, rubbing the sleep from their eyes, would go downstairs to the kitchen, where Grandma Tran was waiting with slices of tasteless, pulpy fruit for their afternoon snack. Thuy was almost happy here; she liked spending time with Grandma Tran, she liked being away from her mother, she liked that she felt vaguely Vietnamese for the first time in her life. She was even starting to like the weird smell of the house. What she didn’t like was the food. She had consumed her stash of American

snacks in two days, and now there were only the same, dull meals to look forward to: dragonfruit for breakfast, then rice or something soupy for lunch, and then more for dinner later, sometimes accompanied by a piece of fish or chicken. Thuy and Kieu never saw Grandma Tran cook—she always prepared the food while they showered and dressed, and when they came downstairs they found it already spread out on the table. Thuy felt guilty because of the element of servitude that subtly infused their relationship with their grandmother—she never ate when the girls did, only stood and watched them from the kitchen counter, and she never let them help with any of the washing up, shooing them away from the garden when they tried to fetch water for her from the pump.

Thuy’s guilt was made worse by the fact that she couldn’t stand the taste of her grandmother’s food. She loathed the food of her people. She spent mealtimes pushing around the contents of her plate and trying not to grimace, all the while dreaming of the food back in America. To be specific, she dreamed constantly of sandwiches. She didn’t know why it was sandwiches that she craved so strongly, but the thought of them began to haunt her, to obsess her. Every time she lifted her chopsticks to her lips, with every spoonful of rice gruel that she managed to choke down, she was constructing imaginary sandwiches in her head: slabs of cheese and pastrami and pink roast beef piled onto thick bread and slathered with mustard and mayonnaise.

By the middle of week two, the thoughts had utterly consumed her. Thuy knew that she was losing weight from eating—or rather not eating—Grandma Tran’s cooking. When she looked in the mirror she saw how her cheeks had lost a bit of their roundness, and if she absently brought her hand to her chest she would be startled by the distinct protrusion of her collarbone. But somehow, she felt heavier than ever. And the cravings would not go away.

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction

The Frangipani Hotel: Fiction